Be of Few Words

Her Majesty’s War on Verbosity

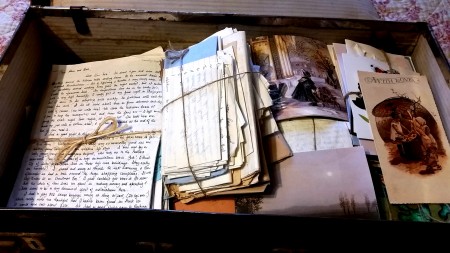

There I was, standing in line at the post office again, my arms full of letters to send home to the United States from Scotland, when the handwritten notice caught my eye. Substantially reduced postal rates would be available for the holidays, the Royal Mail announced, for unsealed greeting cards containing no more than five words in addition to the printed message and the sender’s name.

Five words? Five measly words? Heavens, why bother? I wondered to myself, rearranging the slippery stacks of thick (extra-postage-required) envelopes I was carrying. What on earth could one say that is worth saying in five words or less?

I beguiled my time in the queue by pondering this weighty question. “Merry Christmas—Happy New Year” would of course fit within the required brevity. But unless the cards’ printed message was more than usually beside the point, this would surely be redundant, as well as being rather obvious, and unimaginative in the extreme. There was the urgently telegraphic and classically melodramatic “All discovered—flee at once,” moderately unorthodox as Christmas greetings go but unarguably five words. The awkwardly banal “All well here; how there?” also briefly occurred to me, but on the whole I felt the five-word limit reflected a stinginess unbecoming the Royal Mail and dismissed the matter from my mind.

I beguiled my time in the queue by pondering this weighty question. “Merry Christmas—Happy New Year” would of course fit within the required brevity. But unless the cards’ printed message was more than usually beside the point, this would surely be redundant, as well as being rather obvious, and unimaginative in the extreme. There was the urgently telegraphic and classically melodramatic “All discovered—flee at once,” moderately unorthodox as Christmas greetings go but unarguably five words. The awkwardly banal “All well here; how there?” also briefly occurred to me, but on the whole I felt the five-word limit reflected a stinginess unbecoming the Royal Mail and dismissed the matter from my mind.

Then, unbidden, my memory produced the haunting final message of Etty Hillesum, scribbled on a scrip of paper and tossed from the window of a train bound for the death camps: “Tell them we left singing.”

Five words. Five measly words. Containing whole worlds of sorrow, love, and courage.

So. Maybe it was possible to communicate meaningfully in five words or less. Christmas greetings aside, perhaps there were moments in human experience—and instances in the English language—where the mot juste was just five.

I posted my letters (paying a shocking penalty for the privilege of verbosity) and walked back across town, muttering to myself and counting on my fingers, intrigued as by a crossword puzzle by Her Britannic Majesty’s pentagrammic challenge. I began rummaging in my rag-bag English-major mind for quotations, recalling Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s parallel fives: “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways” (which would presumably have cost her double), and Emilia’s anguished “Who hath done this deed?” from Othello III:5, and Desdemona’s dying (and even more condensed) reply: “Nobody: I myself. Farewell.”

I was hooked. All the rest of that day and well into the following week, I found myself weighing the treasures of the English language in postal scales. I counted (under my breath) the words of my favorite poems, of famous quotes, of conversations heard in the street.

Then I turned my search to Scripture and was overwhelmed by fives. I was astounded to discover, leafing though my Bible, how many of the passages I had marked over the years happened to consist of five words. Many of the most powerful promises in all of Holy Writ are wholly writ in fives. (In English translation at any rate; whether the original Hebrew and Greek are even more austerely economical, I do not, alas, know.)

God’s word to Moses by the light of the burning bush, “I will be with you”; Jesus’ triumphant “I have overcome the world”; and Mary Magdalene’s ringing Easter witness “I have seen the Lord” all are cinquefoil, as it were.

So many of Jesus’ words are familiar to us in clusters of five: “I am the good shepherd,” “Your faith has healed you,” “Rise and have no fear,” “My peace I leave you.” The Hebrew Scriptures as well bloom with five-petaled flowers: “I know you by name,” “I will send an angel,” “Love is strong as death.” Similarly, the vision of Saint John at Patmos—the insight that “death shall be no more”—manages to express one of our faith’s essential convictions in five little words. And there is the divine economy of “light shines in the darkness” and “this Jesus God raised up.” Perhaps my own personal favorite, one wonder of brevity set like a gem in another, is “Jesus said to her, ‘Mary.’ ”

It is not only blessed assurance that comes in quinary, of course. Think of the serpent in Eden, beguiling Eve with “You will be like God.” Or one of Abraham’s least golden moments when, surrounded by lascivious Egyptians, he whispered to Sarah, “Say you are my sister.”

Admonitions seem naturally to lend themselves to pentamerous compression: Scripture positively brims with five-leaved proverbs and aphorisms: “Go and sin no more,” “Serve the Lord with gladness.” Similarly, some of the poignant prayers in the Bible consist of five words: “Lord, have mercy on me,” “Make haste to help me,” “I believe; help my unbelief!” And Thomas, unforgettable, utterly unambiguous, “My Lord and my God.”

Desolation as well seems to fit into quintupled phrases: the devastating “all the disciples forsook him” could be a Holy Week meditation all by itself, as of course could Jesus’ cry from the cross, “Why hast thou forsaken me?” And for me, one of the most perfect visual brushstrokes in the Gospels is the detail from the story of the disciples on the Emmaus road: “They stood still, looking sad.”

The more I browsed, the more I came up with handfuls of fives. Her Majesty’s limitation, which at first had seemed so arbitrary and unreasonable—so ungenerous—began to appear almost recklessly extravagant. After all, so many powerful sayings are compacted into four words—Mother Julian’s visionary “All shall be well,” for instance. And how could Peter have borne another syllable in Jesus’ piercing “Do you love me?”

Come to think of it, some deeply significant affirmations, invitations, promises, dramas, and blessings consist of three words: “So Abram went,” “He is risen!” “Come and see,” “Go in peace,” “Jesus is Lord.”

Or two! I recalled how moved I had been, on the remote Hebridean isle of Iona, by the inscription on the watchtower of the lonely abbey church: “Stand fast.” What compressed sorrow lies in “Jesus wept,” what immensities of self-offering are implied in “Yes, Lord.”

For that matter, didn’t one word often say what most needed to be said? Surely “Alleluia” and “Amen” are all we really need most of the time.

By the end of the week (much of which I had spent secretly counting the words of, and lamenting the excesses of, telephone conversations, newspaper headlines, and public service announcements on the radio), I was convinced that five words—or four, or three, or even two—can speak volumes. Just as a memorable meal can be prepared from a few simple ingredients, so can a feast of meaning be conveyed by an apparent dearth of words. There is a lesson for my loquacious spirit here, a deep learning about fasting and feasting, about self-discipline, about simplicity and silence.

Perhaps Emily Dickinson summed it up when she observed that “the banquet of abstemiousness effaces that of wine” (even if it did take her eight words to say it).