Touched by God

Several years ago, the first harbingers of midlife hit me like a swarm of bees. Suddenly I was forced to stop and pay attention to my body. The attention I paid, at first, was angry, defensive, and ineffectual: panicked, I swatted at the myriad stinging nuisances of hormonal upheaval, sleeplessness, back pain, headaches, and fatigue.

Impatiently I struggled against these evils—and I began to realize that, for many years, I had been treating my body as I treat my car: I acknowledge it as necessary to life as I know it; occasionally I remember to be grateful that I have it. But basically it is external, mechanical, subordinate to my “real” life, which I like to think is lived on the level of the spirit and the mind.

When my car requires maintenance or repair, I resent it. I expect my body, like my car, to operate smoothly and quietly—to get me where I want to go—but it had better be darned undemanding about it.

When my doctor first suggested that massage might relieve much of the lower back pain as well as reduce stress, and perhaps help with insomnia and headaches as well, I was dubious. It seemed a long shot—I was skeptical of “alternative medicine” and the whole new-age business of “body work”—and the process seemed dauntingly expensive both in money and time. But I was persuaded to try it. After all, when a mechanic I trust tells me my car needs an oil change or realignment, I may mutter rebelliously, but I take it in for the service it needs.

That was nearly two years ago. Since then, I have been receiving the benefits of regular therapeutic massage. It has promoted much healing not only in my aging, aching body but in the stiff joints of my theology and prayer as well.

As I allowed the skilled hands of the massage therapist to explore all the tension and pain I was carrying around in my body, I began to realize how carefully I had been carrying my religion in my head.

I was, in fact, surprised and humiliated to discover that I—a lifelong liberal Protestant, long accustomed to deploring the mind-body split fostered by wrong-thinking patriarchal theologians—had been nurturing a mind-body split within myself as deep and wide as the Grand Canyon.

The healing of this inner division came about gradually, almost imperceptibly at first. Integration occurred, as it so often does, completely by grace.

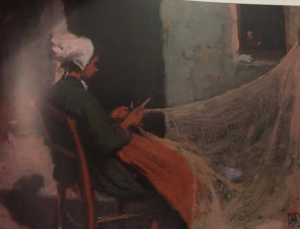

I had been praying the Scriptures early each morning as part of the Ignatian retreat in daily life I had been making, and had lately been meditating on the recurrent image of fishing nets in the Gospels. Peter and Andrew drop their nets to follow Jesus; the disciples cast their nets, pull in their nets. Especially, it had struck me, they mend their nets, frayed and torn by much hard use.

As I lay under a sheet on the massage table that day, meditating drowsily on the image of all those nets, Leah was methodically working her steel-fingered way down my spine. To my weary mind, her probing fingers seemed actually to be unhooking and reattaching each muscle to its vertebra. Something about the soothing repetition of the movement, and the sense of reconnecting muscle, bone, and tendon where they were meant to be, reminded me of watching my grandmother’s crochet hook flash in and out of the afghans she was always either making or mending.

As I lay under a sheet on the massage table that day, meditating drowsily on the image of all those nets, Leah was methodically working her steel-fingered way down my spine. To my weary mind, her probing fingers seemed actually to be unhooking and reattaching each muscle to its vertebra. Something about the soothing repetition of the movement, and the sense of reconnecting muscle, bone, and tendon where they were meant to be, reminded me of watching my grandmother’s crochet hook flash in and out of the afghans she was always either making or mending.

And then, in a flash, I knew myself to be a net, being mended. For a moment, it was Jesus’ own hands I felt on my back, carefully reconnecting the places that had lost their moorings. I had never before permitted myself to imagine Jesus actually touching my body—my mind and heart, yes, of course; I spoke freely, even glibly, of being “touched” in that way—but really to feel the touch of Jesus on my skin was a revelation for me.

It was also a new thought that I, in my flesh and bones, might be valued by God. As valued as a fishing net, anyway. And wasn’t that one of Jesus’ commissioning promises to the disciples, that they would become “fishers of people”?

To the extent that I ever let myself think of myself as useful or precious to God, it was only because of my mind or my work or my words. Proper little Gnostic that I had unconsciously become, I assumed that God valued only the “spiritual” in me.

But maybe—oh, revolutionary thought—Jesus was concerned about the mending and healing of my body as something he cared about, something he valued enough to mend when it was, like a fishing net, frayed by much hard use.

That was the beginning of the healing within me of the separation I had caused between my (unimportant) physical identity and my (important) intellectual and spiritual identity.

But it was only the beginning—God had only begun, that day, to heal my severed sense of self.

Another time, months later, in the midst of a massage, it occurred to me that Leah was kneading the muscles of my calf as though they were bread dough. All at once, spontaneously, I knew myself to be, in my body as well as in my mind, bread in the making, under God’s kneading hands.

Without analyzing it or studying it—completely without benefit of commentary, concordance, or footnote—I knew in my bones that God was at work in me for my own transforming as surely as a woman who stirs a measure of yeast into her flour, a sacramental mystery as deep and as ordinary as bread on the table, bread on the altar, bread in the mouth.

And then again, just the other day, as Leah’s discerning hands were loosening tension in my shoulders, I felt like clay in her hands—clay stiff and resistant at first, but surrendering in trust and gratitude to her shaping touch.

And then again, just the other day, as Leah’s discerning hands were loosening tension in my shoulders, I felt like clay in her hands—clay stiff and resistant at first, but surrendering in trust and gratitude to her shaping touch.

Instantly, the word of God came to me as it had to Jeremiah: “Behold, like the clay in the potter’s hand, so are you in my hand” (18:6). Once again, I felt myself invited to appropriate the formative reality of God at the level of my body, in the reality of my clay-ness, deep in my bones.

The felt reality of God present in my life, creating, healing, shaping at the level of my embodied-ness, has been a great gift to me in middle age. At this point, as never before, I know and feel myself to be in God’s hands—not as a machine to be “fixed” but as a beloved, well-known creature: as earthy and tangible as a fishing net, as bread dough, as clay.

Finally, by the grace of God—by way of meditation and massage—I am beginning to be able, in body, mind and spirit, to honor the God who became flesh, at work and at home in my own flesh and bones.