Deep Waters

Ever since I was a child I have loved shallow water: six inches of sun-warmed Kansas creek sliding about my ankles; the edges of the sea, where tides embroider a new selvage of wonder every day; the margins of lakes, busy with reeds and turtles, birds and dragonflies.

The great thing about shallow water, I realized instinctively as a child, was that I could see all of it, stand dry and upright in it, walk out of it at any moment. Everything between the surface and the bottom was apparent. Shallow water keeps no secrets.

Conversely, I have never much liked deep water. Long before the film Jaws (much less Open Water) made thousands dread the terrors of the deep, I avoided water I couldn’t see through, where anything larger than a minnow was likely to lurk. When as an adult I read John Irving’s novel The World According to Garp, I instantly identified with the child who hears the grownups talking about the danger of the undertow, and assumes it to be a monster prowling beneath the surface: the Undertoad.

There was a tradition in my family, growing up, that put my aversion to deep water to a severe test. Everyone ritually saluted childhood’s end by swimming on a summer night across the Indiana lake where my grandparents had a cottage. The summer I was twelve was my turn, and I dreaded that night swim for weeks beforehand. Although, of course, no one would have forced me to attempt it, the ordeal felt as inexorable as fate. I was as filled with secret horror at the prospect as if I had been commanded to brave the mythical death-dealing depths of the Hellespont, or the fathomless monster-full mere in Beowulf.

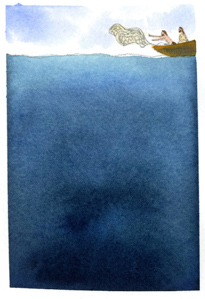

I can still remember that night swim, the cold black water opaque under the moon. Even though my grandfather was rowing alongside me, I was terrified. Like a child afraid of waking the monster under the bed, I kept my strokes as shallow as I could, kept myself as close to the surface as possible, lest I wake the chaos of the deep, the Undertoad.

It is not just in Midwestern lakes that I fear the dark depths of things. It was not only in my childhood that I struggled to stay on the surface, to keep black waters from closing over my head.

Several years ago, during a time in my life of grievous loss, I had a recurrent dream which featured that same grandfather’s rowboat and that same Indiana lake.

In the dream, I was alone in the boat, out in the middle of the lake, far from shore. The boat was leaking badly, water pouring in through cracks in the hull. I bailed frantically, simultaneously trying to steer the boat toward land, running the small outboard motor as fast as I dared. Only by outrunning the leak could I hope to stay afloat. That was the entire dream: the struggle to go fast enough to keep from sinking.

When I told this dream to my spiritual director, she helped me see my fear of the depths of my own sorrow. I was trying as to escape the abyss, rushing ahead on the surface of my life to avoid confronting the extent of my loss. She urged me to revisit the dream’s image in prayer, deliberately stopping the frantic racing and baling, to see what would happen. I did so, although reluctant to invite the result I so much dreaded. Perhaps I secretly hoped that I could manipulate a different ending to the dream—the boat’s gaping wounds miraculously healed, the boat itself brought safe to shore.

In my prayer, the boat (which mysteriously became my self) slowly sank beneath the waves, settling at last on the bottom of the lake. However—unexpectedly—this was not frightening at all, but full of peace, full of God. Somehow in my prayer the fear at the heart of my dream was redeemed and healed—and consequently my fear of my own grief was changed. I felt sure that God was with me, would be with me even at the bottom of the lake, even if I traveled to the deepest limit of my sorrow. And, in fact, that was where God was waiting to meet me.

We would all prefer, I suspect, to live on the sunlit surface of our experience, at the shallow end of the pool, the safe edges of the sea. Nevertheless, it is to deep water that God calls us. “Put out into the deep,” Jesus invites Peter (Luke 5:4).

It is into deep water of one kind or another that we will all be sent. God calls us to our deepest places that we may learn to trust in God-with-us instead of in our own strength. Sometimes those deep waters may be grief so profound that it threatens to drown us. Sometime prayer itself becomes deep water: intercession for those in pain or fear can lead us to share that great darkness, to leave shallow confidence behind. The depths of contemplation may also lead to the uttermost parts of the sea.

Whether the deep water in our experience is that of grief, depression, or the fathomless quiet of contemplative prayer, life won’t let us stay in the shallows. Eventually, one way or another, we will find ourselves where suddenly we can’t touch the bottom anymore. Where maybe we can’t even keep our heads above water. Where we are, in fact, not in control.

This is what the 16th century Spanish mystic Saint John of the Cross in The Living Flame of Love called “Night”—and which Carmelite scholar Iain Matthew defines in The Impact of God: Soundings from St. John of the Cross as “that which comes upon us and takes us out of our own control.”

This is an ancient terror, that has made for ancient prayers. David cried, “Save me, O God! For the waters have come up to my neck, I sink in deep mire where there is no foothold; I have come into deep waters, and the floods sweep over me. …Let me be delivered from the deep waters, let not the flood sweep over me, or the deep swallow me up” (Psalm 69:1,2). Saint John, pondering the shattering experience of Night recounted in this psalm, speaks of it as a kind of disintegration, a “terrible undoing.”

This is perhaps our deepest fear, that we will be abandoned to chaos, that we will never find our way out, that, as another psalmist put it, darkness will be our only companion. We dread being cast like Jonah into the deep, into the heart of the seas: “The flood was round about me; all thy waves and billows passed over me,” Jonah recalls with fear audible down the ages. “The waters closed in over me, the deep was round about me; weeds were wrapped about my head at the roots of the mountains” (Jonah 2:3,5).

But it seems that those dark unmanageable nightmare depths can be the very place that God finds us. The author of Psalm 69 moves from his terrified cries to God for rescue to conclusions of quiet trust and gratitude: “Let heaven and earth praise him, the seas and everything that moves therein” (Psalm 69:34).

The waters of death can be the waters of baptism. The sea of terror can be transformed, as Saint John of the Cross discovered, into a limitless “sea of love” engulfing us. [i]The place of disintegration can, by grace, become the place of saving encounter, of resurrection.

As the psalmist and the mystic knew, as my dream-prayer reminded me, the gift given us in these drowning, despairing moments in the grip of the Undertoad is not the opportunity for control, but for surrender. Even on a literal level it is important not to panic, but to trust: swimmers caught in rip tides who struggle against powerful coastal currents risk exhaustion and death; those who allow themselves to be borne by the tide along the coast will usually find themselves deposited (like Jonah) on a strange shore, weary but unharmed.

This is possible for us, in the deep waters of our lives, because there is nowhere we can go where God is not, and because nothing, neither height nor depth nor anything else in all creation, can separate us from God’s love (Romans 8:39). If we dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea, even there God’s hand will lead us and hold us (Psalm 139:9–10).

In language startlingly reminiscent of my dream-turned-prayer, the 14th century mystic Julian of Norwich describes (2nd showing, 10th chapter) her own experience of being submerged in God:

“Once my understanding was let down to the bottom of the sea. …Then I understood in this way: that if [we] were there under the wide waters, if [we] would see God as God is continually with us [we] would be safe in soul and body and come to no harm. And furthermore, [we] would have more consolation and strength than all this world can tell.”

God is present with us not only in our struggle to keep our heads above water, but—perhaps even more deeply and powerfully—when we stop struggling for control, and surrender in trust to Christ from whom nothing can separate us, who is always present to us whether we are aware of it or not.

Trust is key here. Iain Matthew reminds us in The Impact of God that “to trust—that God is present in this—can turn the pain, where there has to be pain, from death-throes into the pangs of birth.”

God present with us in darkness, far below the surface, is graphically represented in a statue submerged off the coast of Italy. Il Cristo degli Abissi—“Christ of the Deeps”—is a statue of Christ on the ocean floor some forty feet below the surface of the Mediterranean. Jesus raises his arms and his compassionate face to greet those who have come into deep waters, over whose heads the waves have closed, as though to say “Take heart; it is I; have no fear” (Mark 7:50). The statue is visible only to divers (and was in fact commissioned in memory of a diver who died along that coast in the 1950s), so I have only seen it in photographs. I find the image compelling, its unseen presence on the bottom of the sea consoling.

God present with us in darkness, far below the surface, is graphically represented in a statue submerged off the coast of Italy. Il Cristo degli Abissi—“Christ of the Deeps”—is a statue of Christ on the ocean floor some forty feet below the surface of the Mediterranean. Jesus raises his arms and his compassionate face to greet those who have come into deep waters, over whose heads the waves have closed, as though to say “Take heart; it is I; have no fear” (Mark 7:50). The statue is visible only to divers (and was in fact commissioned in memory of a diver who died along that coast in the 1950s), so I have only seen it in photographs. I find the image compelling, its unseen presence on the bottom of the sea consoling.

“Christ of the Deeps” reminds me that what God offers us is not control but trust—not safety but presence.

Julian of Norwich in another of her “showings” (the 3rd showing, 11th chapter) heard Christ say:

“…See I am in all things. See, I do all things. See, I never remove my hands from my works, nor ever shall without end. See, I guide all things to the end that I ordain them for, before time began, with the same power and wisdom and love in which I made them. How should anything be amiss?”

I still prefer the sun-warmed clarity and sure footing of shallow water. I probably always will. I shall doubtless pray many times before I die to be delivered from deep waters, that God not let the deep swallow me up. But when the floods inevitably sweep over me, I hope I will also trust that God will be present in, and beyond, all my dyings.

My fear of the abyss no longer paralyzes me, because I believe that Christ is in all things, loves all things, and never removes His hands from what He has made. He will be waiting for us at the furthest edge of any darkness.

[i]The Living Flame of Love, stanza 2:10 The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross, p. 661.