Thanks be to God:

Gratitude as Prayer of Adoration

Several years ago, at the invitation of an old friend, I joined her in an unusual email correspondence: every day, we agreed, we would exchange short lists of particular things in our lives for which we were grateful. “Particular” was mandatory: no vague generalizations about good health or pleasant weather were allowed. Our identified blessings might be small, but they had to be specific: a ripe peach at breakfast, a family quarrel resolved, a finch’s nest discovered outside the kitchen window, a lost letter found, a tedious task accomplished.

Soon after beginning this regimen of gratitude, my friend fell and broke her arm; I underwent surgery to repair a torn tendon in my shoulder: we kept careful track of every minuscule gain during our recoveries, noting each small step out of disability and pain not only as milestone but as gift.

We realized, as we taught ourselves systematically to account for all we might be thankful for under those circumstances, that gratitude is not simply an easy emotion or obvious response: it can be a challenging discipline, with far-reaching implications for the way we see the world.

Scientists are beginning to recognize the potential consequences of habitual gratitude for human health and well-being. Cognitive psychologists urge their patients to list things they are grateful for as part of a process of behavioral modification—an exercise which trains those who may be habitually discouraged, resentful, or exhausted by depression, to begin to see patches of light in the prevailing darkness, to be able to shift from a dominant attitude of negativity to a more positive approach to their situation.

My wise grandmother used to admonish me when I complained about some childish misfortune, “Count your blessings, missy.” She was right: focusing our attention on our blessings can, as research now demonstrates, yield increased energy and optimism, better physical health, relief of depression, measurable progress toward personal goals.i My friend and I certainly found this to be true: as we deliberately sought out specific blessings in our lives, we began to see how lavishly those blessings were strewn across our paths. We began to be more grateful, more cheerful, more patient with others and ourselves.

Gratitude, in other words, “works.”

But practicing gratitude is not just “effective” in a short-term utilitarian way—it can also transform the way we see and live and pray, can transform our very selves.

What began as a simple accounting of the mercies in our lives—that we might give more authentic and specific thanks for them—gradually came to change not only what we saw (“things” to thank God for) but how we saw them (with amazement, joy, love, and praise). Saluting a greater number of the manifold blessings half-hidden in the landscape of our daily lives (a simple quantitative change, as a birdwatcher might add a hitherto un-seen bird to a life-list) led us—without our really intending it—to a qualitative change of perception.

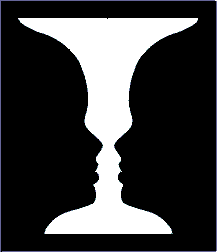

It was (in those early days) as though we were looking at Rubin’s “vase-faces”—those cognitive optical illusions developed by the Danish psychiatrist Edgar Rubin early in the 20th century, in which what may first appear to be an image of a vase or goblet may subsequently be seen (with no change in the image itself) as two human faces in profile.

It was (in those early days) as though we were looking at Rubin’s “vase-faces”—those cognitive optical illusions developed by the Danish psychiatrist Edgar Rubin early in the 20th century, in which what may first appear to be an image of a vase or goblet may subsequently be seen (with no change in the image itself) as two human faces in profile.

Rubin demonstrated with these images that we do not automatically “see” anything: our brains shape what our eyes observe. What at first might seems just a picture of a light-colored vase against a dark background can also be seen as two dark faces looking at each other against a light background: the positive image and its negative counterpart both present at once, both available to our perception, but one—at least initially—more difficult to recognize.

We interpret reality. We make choices all the time about what our eyes perceive, and—significantly—we can train that perception, can learn to see in new ways, can become aware of both the figure of the vase and the independent validity of the field that surrounds it. By the same token, we can learn to see grace in all things. Changing ourselves begins with changing our perspective. As C.S. Lewis pointed out, “what you see…depends a good deal on where you are standing: it also depends on what sort of person you are.”ii

That is the second gift our practice of gratitude gave my friend and me: over time we came to see not only the glass of blessing of our lives as half-full rather than half-empty—which requires only a simple shift of attitude—we came to see more deeply into the mystery of things. We began to see (as Dr. Rubin might say) grace as both the figure and the ground of our lives, surrounding and pervading and defining everything. The eyes of our eyes were opened, as the poet e.e. cummings put it.iii In Saint Paul’s even apter phrase, the eyes of our hearts were enlightened (Ephesians 1:18).

A habit of gratitude, then, can give us a more positive outlook on life. More than that, it can actually change the way we perceive reality, can open our eyes to grace hidden in plain sight. But gratitude is not just psychologically effective self-help, not just a way to deepen our awareness of the real nature of our experience. Gratitude is also, interestingly, enjoined upon on us almost as a commandment.

For Jews and Christians, who know God to be the fount of all blessing, gratitude has always been an essential (even though implicitly difficult or costly) part of worship. We are to make a “sacrifice” of thanks and praise to God (Psalm 50:23, Psalm 116:17; Hebrews 13:15)—which certainly suggests that such gratitude is not always spontaneous or easy. Saint Paul insists that it is not just for the obviously good things, or in the obviously fortunate circumstances, that we are to thank God: “We must always give thanks to God” (2 Thessalonians 2:13); “give thanks in all circumstances” (1 Thessalonians 5:18); “give thanks to God the Father at all times and for everything” (Ephesians 5:20).

Why would our faith insist that we always, in all circumstances, give thanks to God? Of course God does not—like some petulant despot whose vanity must be constantly appeased—either require our perpetual flattery, or command that we deny heartbreaking reality and somehow feign gratitude for calamities.

I now suspect that the wisdom behind the insistence on giving thanks at all times may be linked with the insight of Dr. Rubin’s vase-face experiment: we must come to see that both the figure and the ground of our experience are real and discernible, and full of meaning: full in fact of God. We must not only thank God for the “good things” that happen to us but be willing to seek God present with us in the “bad things” as well.

Otherwise, as Henri Nouwen points out, we tend to divide our lives into “good things to remember with gratitude and painful things to accept or forget.”iv We are usually willing to find God in, and be grateful to God for, obvious blessings (the “figure” in Rubin’s experiment). We may need practice to see that God is also present in the background (the initially hidden “field”), giving meaning and hope even in the darkest and most difficult times.

God’s invitation to us—and the third, most precious gift of a habit of gratitude that extends to “all times and everything”—is to realize that in fact there is nothing outside the realm of God’s mercy, that everything is grace, that “there is faithfulness at the heart of all things.”v

In fact a discipline of gratitude offers far more than psychological benefits, and transcends religious duty. For Christians, it offers an opportunity to deepen our intimacy with God, to focus our awareness of—and trust in—God present with us in love and faithfulness—inseparably, at all times and in all places.

“Counting our blessings” can lead to a change of attitude, then to a change of perception itself. Finally, a practice of gratitude can lead to a profound change of heart. We can glimpse the truth of William Blake’s insight that “gratitude is heaven itself.”vi

In this landscape of prayer—which is the landscape of our ordinary lives—little tributaries of gratitude can pour into great rivers of adoration, and lead at last into the unfathomable depths of contemplation.

This journey to the eternal seas usually begins with the smallest streams.

For C.S. Lewis, connecting gratitude with adoration began with an actual stream in a forest he encountered on a walk with a friend. As they walked, they had been discussing Christian worship, particularly the centrality of adoration. Lewis claimed that one should begin prayer of adoration by summoning up everything “we believe about the goodness and greatness of God, by thinking about creation and redemption and ‘all the blessings of this life.’” But his friend, objecting to this abstract hypothetical approach, turned to the brook beside them and splashed his face and hands in the little waterfall, asking: “Why not begin with this?”vii

Spontaneous delight in the sheer gratuitousness of natural beauty leads naturally to gratitude, and thence to adoration. The “cushiony moss, the coldness and sound and dancing light” of that woodland stream, Lewis realized, “were no doubt very minor blessings compared with ‘the means of grace and the hope of glory.’” But the moss and the water and the dancing light were not theoretical, they were tangible and fully present to his senses: “they were manifest: they were not the hope of glory; they were an exposition of the glory itself.”viii

Appreciation of the gift of any good thing can lead us to love of the Giver. Awareness of blessing leads to adoration, as Lewis points out: “One’s mind runs back up the sunbeam to the sun.”ix

Even these small and ordinary pleasures can be what C. S. Lewis calls “patches of Godlight in the woods of our experience”x—the first steps on the way from simple gratitude for a gift given, to the depths of contemplative, self-surrendered adoration of God for God’s own sake. As the Benedictine monk and writer David Steindl-Rast has observed, “Gratefulness is a school in which one learns love.”xi

And we must begin, as Lewis did, where we are: with the concrete and particular.

The more we grow in gratitude, the more we see that it is God alone who authors all the blessings in our lives, the more we come to trust God’s love and goodness “at all times and in all places.”

And that is what will lead us into the darker holiness of gratitude that can sing underground, that can, as Saint Paul insists we must, “give thanks in all circumstances.” Eventually, by making a habit of gratitude, we can come to rejoice in the presence of the Giver even when there is no apparent gift, when only trust in the ultimate mercy of God remains.

I have not yet been required to go to that austere place where faith abides when all else is lost. But I have come close enough, from time to time, to see that county from a distance. I have had a glimmer of the faith of the saints and prophets who can say in the face of utter desolation: “Though the fig tree do not blossom, nor fruit be on the vine, the produce of the olive fail and the fields yield no food, the flock be cut off from the fold and there be no herd in the stalls, yet I will rejoice in the Lord, I will joy in the God of my salvation” (Habakkuk 3:17–19).

I am not there yet. Those heights and depths of abandonment to divine providence are still far ahead of me. But I believe that we find deep joy as we learn to give thanks in all circumstances, “the joy of courageous trust, the joy of faith in the faithfulness at the heart of all things.”xii

That is where this river runs, and I pray—with daily gratitude that God has brought me safe thus far—that I am on the way to those silver seas where God is all in all, where gratitude is heaven itself.